Belgica120-Arrival

After two days of traveling we have finally arrived in Ushuaia. Ben (our skipper) picked us up from the airport. Even though we were tired and exhausted, we went directly to the harbour and had a first look at the Australis, the ship we are going to call home for the next few weeks. Stowing away all our equipment and luggage was another challenge, however now is everything is packed and ready. Customs clearence tomorrow … planned departure on Sunday the 25th!!

Belgica120-Departure

Time is a relative thing. We left Belgium only 4 days ago – feels much longer with all that happened. Now, it accelerates again, throttle down and off: last dinner, shower, night, and right now breakfast on land. We got a security briefing yesterday already. Departure within the next hour. Approx. 8h until Cape Horn and then enter the Drake Passage. Drake lake or Drake shake? Either way, here we go!

Wednesday 21st February

For this last day on the field, we decided to look further west from the station, an area we haven’t sampled yet. Smalegga Mountain proved to be a suitable location, as well as a significant point of interest, as it was at the foot of this mountain that the 1959 Belgian Antarctic expedition left a sledge. Once at the top of the first crest from the ski-doo track, we noticed a glacially eroded surface covered with fine-grained material, which is an ideal sampling site for micrometeorites. After taking the sample back to the laboratory of the station, we quickly found our first cosmic spherule of the day. However, it also turned out to be our last micrometeorite in this sample. Once back in Brussels, we will have more time and better equipment to determine the quality of this sample.

Now we keep busy preparing our trip back to Belgium, packing and labelling all the samples we have collected on the field. A tedious task, but an important one nonetheless.

After 450 km on the skidoo and 105 kg of sampled sediment, our Antarctic adventure has come to an end. As they say in French: “ce n’est qu’un au revoir!”.

Steven and Matthias

Belgica120-Buenos Peres

We arrived safely in Buenos Aires. After 14h of flight, the warmth and humidity of northern Argentina is giving us a brief respite before it is getting colder again. Having one day to our next flight (to Ushuaia), we are using the time to explore the city, having brief science meetings for some of us (Charlène) and generally stacking up on sun and warmth.

Belgica120-Checked in!

Some gear is already in Ushuaia, the remaining stuff is now ready for our flight from Paris. We checked it in already at the train station in Brussels. That was a good call – we did have a lot of extra bags and weight, especially due to all the diving equipment. My little bag has now a heavy lead belt on top. Hope nothing gets crushed… Next stop Buenos Aires!

February 20th 2018

On Tuesday, we visited Wideroefjellet, where we know micrometeorites are abundant based on an earlier expedition in 2012. To reach a ridge near the highest summit of the Sør Rondane Mts., of course we need to make a small effort and climb this monster using crampons, ice picks and snow poles. We reach the ridge in 2.5 hours. The weather is good, yet the wind-chill factor goes down to -30˚C near the sampling site. Exhausted (except for robot Raphael!), we start our sampling. Even in only 5 years, this site has changed with significantly more snow accumulation. The soil and underlying rock are frozen, and we need to use the chisel and hammer to collect fine-grained sediment. Matthias points out that the other side of the valley may also be a good site to sample. Reluctantly, as it’s getting late and temperatures are starting to go down, we move in that direction to discover that this is indeed a perfect location! With backpacks full of sediment, we move down to the skidoo parking spot in 1h15m and return to the station after a skidoo ride of 1h. No need to say that again the collected samples appear full of micrometeorites using the microscope at the station?

What are we going to do with all these samples in the range of 70 kg? Well, pick out all the micrometeorites of course! Because the larger a micrometeorite collection is, the more chances of finding extremely rare material. Just think of unmelted micrometeorites, rare achondritic micrometeorites, airblast particles…? Who knows what secrets this now very large collection holds?

February 18th and 19th

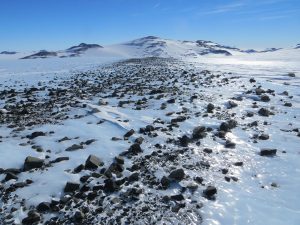

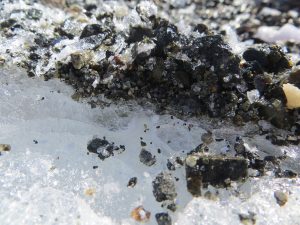

On the fifth day of the expedition, the target was a supraglacial moraine located near Walnumfjellet, which is the most micrometeorite rich site we have found so far. Previous moraine sampling has proved to be reasonably successful, so aiming for this moraine in particular made sense. Much to the surprise of the team members, what we found upon arrival to the site was a line of sparse rocks partially enclosed in ice, with no fine-grained material to be found. Steven and Raphael decided to take this opportunity to sample ice along the blue ice field the moraine was running along, while Matthias decided to explore the moraine further to find a micrometeorite sampling site. After walking along most of the moraine, only one suitable sampling site was found, which consisted of a centimeter-thick layer of icy fine-grained material. Upon returning to Princess Elisabeth Station, we stopped on the ridge of the Svindlandfjellet to sample more fine-grained material. Upon examination of the moraine in the laboratory, it turns out that this unique sample in surprisingly rich in micrometeorites! The sixth day of the expedition was a very demanding one, as it involved sampling ice along a steep glacier close to Wideroefjellet. But it was worth the effort, as these 22 samples will allow a better characterization of the ice dynamics in the area.

Belgica120-Gear

The countdown’s ticking very fast… only two days until departure in Brussels. In the meantime our scientific equipment has already arrived and was taken aboard. Hooray! Sending oftentimes valuable, sometimes unique (think ROV, special diving & fishing devices, …) gear half way round the world and back can be challenging, to say the least. A lot of administration and paperwork (and patience) is needed to get everything on track. Luckily our chief has been very persistent and eventually managed to master the bureaucracy jungle attached to the task. So, now it’s there and we have some graphic proof, which is great… but, hey, wait what is that?! What happened to our box (very solid and sturdy aluminum box that is)?

Things rarely go as planned with end of the world exploration. And so our first surprise is an equipment box already punched in before it even got on board. We’re still lucky though. Nothing absolutely crucial seems to be in that box and also while the box itself has definitely changed shape, the content seems largely intact. Phew. Back in Europe our next immediate challenge is to not overload our bags and get everything checked in.

Henrik.

Saturday 17th February

The weather was exceptionally good today, so we decided to take a long ski-doo trip to Walnumfjellet, a group of small mountains located 70 km from Princess Elisabeth Station. For this very technical trip, amongst glaciers leading to the high plateau, we were lucky to have Alain Hubert as our guide, next to Raphael. After a long ride, we eventually reached our destination, 2400 m above sea level and with wind-chill effects reaching -28°C. We quickly noticed glacially eroded summits popping out of the ice, which looked like ideal sampling sites. The cold temperature motivated us to quickly get to work, sampling a very promising looking fine-grained detritus. Promising because the surfaces of these flat summits have been stable and potentially exposed to the sky for approximately 2 million years, during which we surmise that they have been accumulating cosmic dust falling from the heaven. After sampling 5 different sites, we made our way back to the station, through steep glaciers and long stretches of icy flatland. Once back, we couldn’t hold our excitement and started looking through one of the sample. Much to our amazement, we found more than ten micrometeorites in less than 15 minutes, making this sample exceptionally rich. We can finally say that braving the cold and lack of oxygen was a small price to pay for such an exceptional find and day.